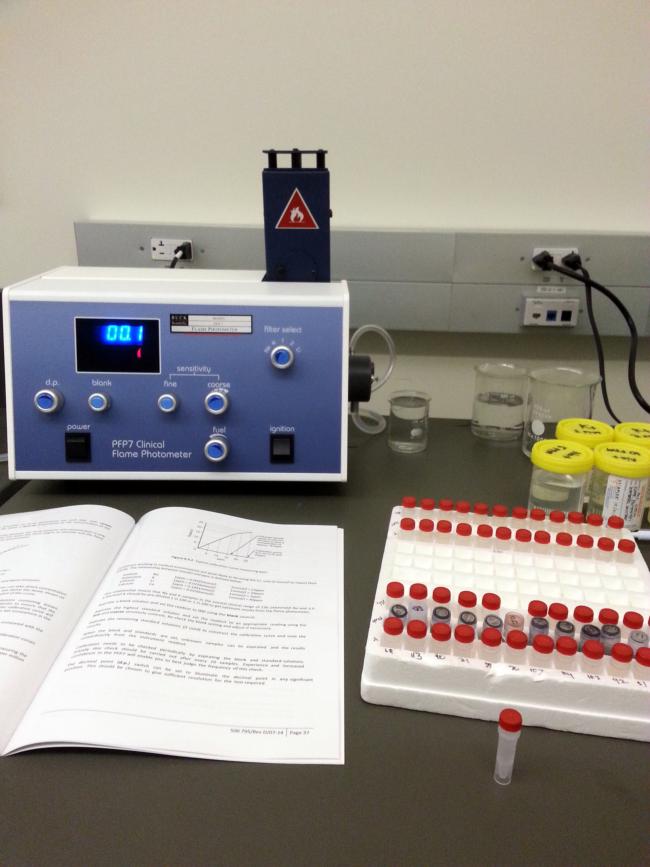

It’s been an exciting time for the shark team at the Cape Eleuthera Institute with 2 tagged sharks recaptured over the past few weeks. The team has been conducting frequent long line surveys to collect information about the species, sex and size of the sharks that inhabit the waters around Eleuthera. DNA, blood and muscle samples are also collected from each shark to build up a wealth of biological data which can be used for more in depth studies in the future.

CEI tags all of the sharks that are caught on their longlines with 2 different kinds of tags, a dart tag and cattle tag, which assign an individual tag number to each shark. This not only allows the shark to be easily recognized by the shark team, but also shows other people that these sharks have been caught and sampled by CEI. The tags provide the CEI contact details to allow other research stations or fisherman that may catch the shark to report its location. This recapture data allows the team to analyze distribution behaviors and track the movement of the sharks around Eleuthera.

The most recent recapture was of a female Caribbean reef shark (Carcharhinus perezi) which was caught on the 31st of October, only 300m away from where it was first caught in April 2010. Over the past 6 years this shark has grown by nearly half a meter and now measures a total length of 178cm. A few weeks earlier, on the 12th of October, the team caught a large female nurse shark (Ginglymostoma cirratum) that had not been seen since it was first tagged nearly 8 years ago. This shark had only grown by 3cm over this time but was recaptured nearly 6km away from where it was originally caught and tagged.

Using species-specific size at maturity data, the team can use the total length measurements of these 2 recaptured sharks to estimate that both sharks have recently reached sexual maturity. This is particularly important information when considering the local populations of these sharks as they are now thought to be of reproductive age. These resident sharks will remain around the Cape and contribute to local populations by giving birth to several pups in the mangrove creeks surrounding Eleuthera.